Why I created Redux-Tiles library

Recently I published Redux-tiles library, which itself is a pretty small library intended to fight the verbosity of original style Redux. If you are just interested in code, feel free to take a look at examples, otherwise let’s go slowly.

What is Redux?

Redux itself is an implementation of Elm-style app architecture, where we store state in an instantiated object, and then apply functions with specific type to this object, and another function, called reducer, reacts to this specific type. Such complicated architecture guarantees that data flow is unidirectional (just mutating this object won’t change anything), and it makes it much more complicated to shoot in the foot.

Redux is a great library, but in it’s raw state it actually often frustrates people (especially newcomers). It is pretty confusing in the beginning, and restrictions seem too strict. The core idea is that we have unidirectional data flow, and data itself can be changed only in one place (registered reducer for this part of the state), and therefore we can always trace (or simply recreate steps) how something was changed.

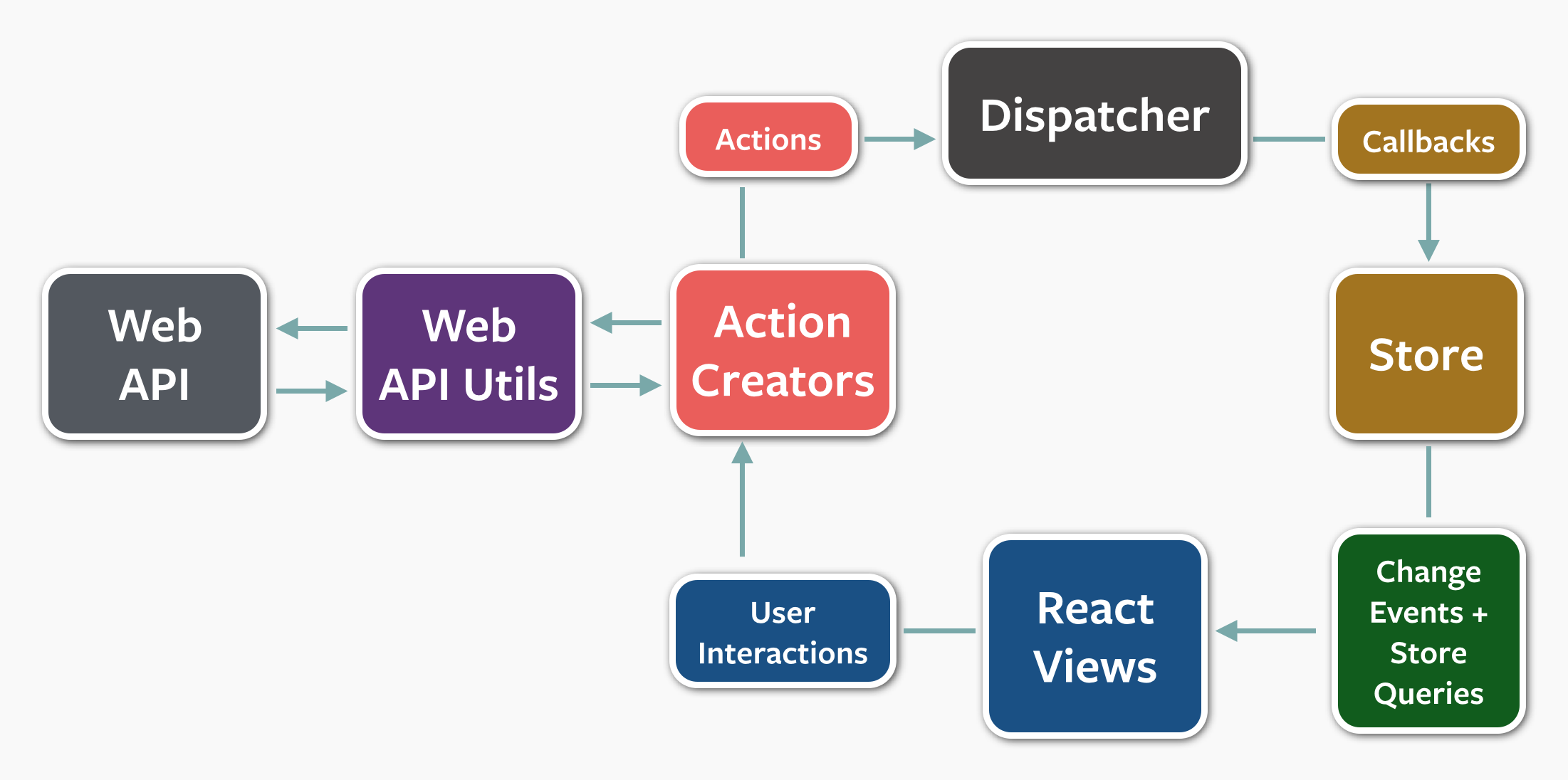

The classical diagram looks something like that

The classical diagram looks something like that

Initially it was presented on React Europe 2015, and then it conquered the world (adaptions appeared in many languages). Nowadays it is a de-facto standard in React community, and even the creator (who was coincidentially hired by Facebook) tries to persuade people that they might not need Redux. Redux is heavily inspired by functional programming concepts, so some purists tried to put everything inside it, completely discarding local state.

You Might Not Need Redux https://t.co/3zBPrbhFeL

— Dan Abramov (@dan_abramov) September 19, 2016

So, while redux solves many problems (like updating number of notifications in different parts of the application), it also brings several new. One of the biggest problem is large amount of concepts, even for small things – you have to create constants, actions and reducer; again, even in case if you want just to store some data. Also, imagine a situation, when you have 2 actions, let’s say obtaining user’s token and then authorization. Technically, both of these actions actually belong to another action – logging in, and we might just do two requests in the same action (to save our time and to write less code). The problem here is that at some point we might need to do only token request, and then things start to be more messy. Also, we might want to make UI more responsive, and actually provide status info, “checking your credentials” and “authorizing applications”, and to do this we’d have to add at least one more whole package – constant, action and reducer (we can handle second state checking first and loading of the login), but sooner or later it will bite us.

For instance, typical async action will look something like this:

| // this is a typical redux action declaration. We usually globally require api | |

| // (or other modules), and declare/require constants | |

| import api from '../api'; | |

| const LOGIN_START = 'LOGIN_START'; | |

| const LOGIN_SUCCESS = 'LOGIN_SUCCESS'; | |

| const LOGIN_FAILURE = 'LOGIN_FAILURE'; | |

| const action = function login(params) { | |

| // let's assume we use redux-thunk for async stuff | |

| return async (dispatch, getState) => { | |

| dispatch({ | |

| type: LOGIN_START, | |

| }); | |

| try { | |

| const tokenPayload = await api.post('/user/token', params); | |

| const authPayload = api.get('/user/authorization', { token: tokenPayload.data }); | |

| dispatch({ | |

| type: LOGIN_SUCCESS, | |

| payload: { | |

| token: tokenPayload.data, | |

| auth: authPayload.data, | |

| }, | |

| }); | |

| } catch (e) { | |

| dispatch({ | |

| type: LOGIN_FAILURE, | |

| error: e, | |

| }); | |

| } | |

| }; | |

| } |

| // Typical redux reducer usually contains initial state and then | |

| // merging of new data depending on the constant | |

| const initialState = { | |

| isPending: false, | |

| error: null, | |

| data: null | |

| }; | |

| const reducer = function loginReducer(state = initialState, action) { | |

| switch (action.type) { | |

| case LOGIN_START: | |

| return { | |

| ...state, | |

| isPending: true, | |

| }; | |

| case LOGIN_SUCCESS: | |

| return { | |

| ...state, | |

| isPending: false, | |

| data: action.payload, | |

| }; | |

| case LOGIN_FAILURE: | |

| return { | |

| ...state, | |

| isPeding: false, | |

| error: action.error, | |

| }; | |

| default: | |

| return state; | |

| } | |

| } |

Problem’s solultions

The problem is pretty well-known, and it is not about absence of solutions, rather absence of standard. The idea of modules is fairly common, for example ducks-modular-redux is pretty popular. Also, there are plenty of other solutions, but they are pretty customized. I personally think the problem lies inside normalizr, which was popularized in the beginning of redux, and was often referred in initial tutorials hand by hand. It literally forces you to use redux as a database – creating entities, parsing responses and putting ids instead of values. This is an interesting idea, and actually pretty good if you are working a lot with “collections” – entities, which are often queried, have nested objects, and filtered by similar parameters; but it adds another magnitude of complexity for redux, and makes it literally impossible to somehow put common ground for all possible implementations.

I worked with different APIs, and with different codebase sizes, and my personal opinion is that if you have a big application with pretty specific API, you should create your own small library to grasp your domain. Sometimes it might be beneficial for you to inject inside normalizr behaviour, sometimes you’d need agressive caching, something you won’t need it, but in general, it is much easier to custom-tailor in case your needs are pretty specific. You can use whatever data structures you want, parse data as you need, accumulate requests as you want, and so on. So, with this knowledge in mind, let’s try to list other possible options, for which we create redux modules:

- normal sync operations, which don’t require api requests. For example, notifications – we render them, and after closing we remove them from store

- usual async stuff, which we’d like to track – loading, errors and successfull response

- nested variations of previous options – when we’d like to keep the same logic and data, but nested under different keys:

The whole purpose of redux-tiles is to solve all these cases in easy, composable way, which will allow to test corresponding logic. With traditional approach, especially with nested data, we often have to test merging logic, which is not actual business logic; I think it makes much more sense to isolate our actions, inject through middleware all dependencies, and then test them separately. In this scenario merging and caching are delegated to the library, and it allows us to focus only on our business logic.

Explanation

The library itself contains pretty small amount of magic (mostly in caching part). It is divided into two main parts:

- “tiles” (so-called modules, which contain actions, reducer and selectors)

- helper functions to wire them together (

createEntitiesto combine all of them,createActions,createReducerandcreateSelectors, if you want to have bigger control, andcreateMiddlewarefor injecting middleware)

Tiles create needed nesting (for example, ['user', 'token'] will be conviniently nested in state under { user: token: { isPending... } }), and get function to process data. There are two types of tiles – sync and async, and async tiles by default provide updating state, tracking isPending and error fields. Also, both types support nesting of the data, so if you need to separate data by id, you’ll have just to add nesting: ({ id }) => [id] property to tile’s declaration.

Tile returns everything you passed via reflect property, so you can easily test both nesting and the main function.

You also get dispatch option (and I encourage to pass actions and selectors to middleware as well), so you can dispatch other actions.

Helpers are needed mostly to combine list of tiles, so they will be nested correctly (remember, we can specify arrays of arbitrary nesting in declaration) – they will be available under the same nesting. Also, the easiest way to use is to just use createEntities, which will create you all needed entities. It is also possible to integrate it into existing project – just pass namespace, under which you want to keep redux tiles inside state, as a second parameter to the createEntities or createReducers.

Library provides you a middleware creator, which gets an object to be passed to all dispatched tiles’ functions. Middleware is needed to deal with a function, which will be returned from an action – and this is a precise description of redux-thunk, and while it is a great library, it does not allow you to inject more middleware, which I’d recommend to do (to do DI). Also, usage of createMiddleware will give you a free caching of pending requests, so they will wait (the same promise), without additional requests.

And finally, one of the biggest pain points of modern SPAs – prefetching of data, here is solved via middleware. So, if you use createMiddleware, and instantiate store for each request in your Node.js application, you can dispatch all needed actions, and then waitTiles function will return a promise, which will be resolved after everything will be fetched.

Back to examples from the beginning of the article, now it is the time to take a look how it is used. Here I specify redux tiles for HN API, with pretty agressive caching:

| import { createTile } from 'redux-tiles'; | |

| export const storiesTile = createTile({ | |

| type: ['hn_api', 'stories'], | |

| fn: ({ api, params }) => api.child(params.type).once('value').then(snapshot => snapshot.val()), | |

| // we separate list of stories by type, so we can reuse it for different types | |

| // e.g. topstories, new, etc | |

| nesting: ({ type }) => [type], | |

| // with active caching we can safely fetch it each time for each page | |

| // no additional requests will be done | |

| caching: true, | |

| }); | |

| export const itemTile = createTile({ | |

| type: ['hn_api', 'item'], | |

| fn: ({ api, params }) => api.child(`item/${params.id}`).once('value').then(snapshot => snapshot.val()) , | |

| nesting: ({ id }) => [id], | |

| caching: true, | |

| }); | |

| export const itemsTile = createTile({ | |

| type: ['hn_api', 'items'], | |

| fn: ({ dispatch, actions, params }) => | |

| Promise.all(params.ids.map(id => | |

| dispatch(actions.hn_api.item({ id })) | |

| )) | |

| // there is no need to cache this instance, because caching will | |

| // work one layer down – when we will fetch individual items | |

| }); | |

| export const itemsByPageTile = createTile({ | |

| type: ['hn_api', 'pages'], | |

| fn: async ({ params: { type = 'topstories', pageNumber = 0, pageSize = 30 }, selectors, getState, actions, dispatch }) => { | |

| // we can always fetch stories, they are cached, so if this type | |

| // was already fetched, there will be no new request | |

| await dispatch(actions.hn_api.stories({ type })); | |

| const { data } = selectors.hn_api.stories(getState(), { type }); | |

| const offset = pageNumber * pageSize; | |

| const end = offset + pageSize; | |

| const ids = data.slice(offset, end); | |

| await dispatch(actions.hn_api.items({ ids })); | |

| return ids.map(id => { | |

| const data = selectors.hn_api.item(getState(), { id }); | |

| return data; | |

| }); | |

| }, | |

| // we can safely nest them this way, and be sure that individual items will be cached | |

| // so, changing number of items on the page might not even require a single new request | |

| nesting: ({ type = 'topstories', pageNumber = 0, pageSize = 50 }) => [type, pageSize, pageNumber], | |

| }); | |

| // same strategy for user, as for the item | |

| export const userTile = createTile({ | |

| type: ['hn_api', 'user'], | |

| fn: ({ api, params }) => api.child(`user/${params.id}`).once('value').then(snapshot => snapshot.val()), | |

| nesting: ({ id }) => [id], | |

| }); | |

| export default [ | |

| storiesTile, | |

| itemTile, | |

| itemsTile, | |

| itemsByPageTile, | |

| userTile, | |

| ]; |

Also I am thinking that it is possible to separate tiles as npm modules, and just distribute them with corresponding api middleware, but still not sure whether it is a good idea or not.