State of the art in CSS

This article touches on the latest trends in CSS for big web applications (usually SPA). I don’t try to question whether it is the right or wrong direction, rather try to list all of them.

Originally, web pages were designed to be informational pages with hyperlinks (even images should not be inlined – it is explained by the fact that in 1990, bandwidth and computer resources were very small): something like interactive books. CSS was designed to be able to add some basic styling, and originally it seemed like a good idea to have your own personal styles, which would override the external styles. Nowadays, it is definitely a crazy idea – to try to apply your own styles to, let’s say, headers – developers definitely don’t expect it from users.

One of the funniest things is that it was pushed by Microsoft, you can read about it here – this is a very extensive article, but I’ll skip this initial part, and go straight to important milestones.

Big applications

Historically, frontend was considered a second-class citizen, and very often it was implemented by designers or by special people, who often did not know a lot about programming – usually it was some template language for some backend. Back more more than 10 years ago, it was not that big of a problem, because the size of a typical web app was not big, so styling using classes worked fine enough. Not ideally, but not that annoyingly – though the interest in the Internet was growing, and applications were becoming bigger and bigger, and at some point, people started to realize that CSS has a list of problems, which were becoming more and more serious:

- specificity hell – new rules can accidentally override some old styles, and usually it happens in absolutely unexpected places

- running out of class names – in big applications, it is very easy to accidentally reuse some class name (like

header,content,container, etc) - fragility – dangerous to add new rules/change old ones, because we are unsure how it might affect our project in all possible places

- big files – while it is better to keep everything in one file (so that the browser won’t spend any additional roundtrips establishing connection with our server), it is really hard to maintain one big file

- verbosity – we have to repeat many things constantly (for example, if we want to add

text-overflow: ellipsis), and it is hard to change them lately. Same class might not work because we might want to pass some parameter - no way to share variables with application code – we can hardcode them in both places, but if we want to change, there is a big chance of missing something

CSS is not a programming language – despite introducing variables, there is no functionality for functions, conditions and loops, so there is no way to somehow automate code generation. In case you create class names based on some properties in your code, you have to repeat all of them in your CSS code, and this is inevitable. Same is true for variables, so it is especially painful if you need to change all “green color”, to a slightly different one – sometimes colour might be the same, but semantically it is a different colour (e.g. primary vs header-title). All of this led to the development of preprocessors, languages very similar to CSS, but with extended capabilities – SASS, LESS, Stylus and PostCSS.

Preprocessors

In computer science, a preprocessor is a program that processes its input data to produce output that is used as input to another program. Wiki

List of essential features:

- Variables (one of the most important things!) – so colours and sizes are now semantic

- Imports – they create one big file, which is better than CSS’ approach to just download all imports, establishing a new connection for each new file.

- Loops – allows to create repeated styles pretty easily, for instance, it allows you to create/change grids in an extremely simple manner.

- Functions (or, more often called mixins) – allows to share the same functionality with different parameters pretty easily

- Nesting – allows to keep related styles together, and removes the possibility of error when we write nesting by hand in CSS

Preprocessors definitely help with verbosity, separating styles to small files (they all encourage concatenation into one file) and keeping variables in one place, they do not help you at all with specificity hell and fragility. In order to address these issues, a number of so-called methodologies were invented and popularized.

Methodologies

All methodologies mostly tackle the problem of global class names (so possible overlapping) and specificity hell. Because CSS lacks any scoping, we have to work around this issue, using some form of class name rules. They all have a different approach, but the idea is kind of the same – we use some prefix based on some rules.

For example, let’s take a look at the BEM approach. It is more than a CSS methodology, but we will take into consideration only the naming rules. BEM stands for block, element, modifider; let’s look at a small example. For instance, we want to style the header (which appears to be the last one, which is bold) in the list inside the footer. So we have the following components:

- Block –

footer - Element –

list-header - Modifier –

last

So, the complete classes will be footer--list-header footer--list-header__last. It is pretty verbose, but it allows us to write meaningful class names and (to some degree) non-colliding class names. Also, you can see that the element here consists of two logical parts, so it would be nice to do so, but because we have only these 3 parts, it means we will need to separate another block, footer-list, and inside it we can have an element header. I understand, that a lot of people will say at this moment, that I have no idea what BEM naming is, but it is all just details with the same result – we have unique prefixes, and it helps us to avoid name collisions in exchange for verbosity.

BEM approach does not encourage any nesting, and in case you need to share some styles, in the context of this approach you need to share components, not just class names. Other approaches use nesting, but they have strict rules what to nest and with which classnames.

The problem is that they solve the problem of global variables only partially. We still need to use them, and we avoid problems by making them longer using special rules, and this is not a very reliable solution in the long run. It works, though, so in case you cannot use CSS modules (which adds prefixes automatically), definitely check them out.

I’d like to point out, though, that BEM, by discouraging any nesting, solves a problem of specificity almost completely – but, as always, in exchange for the removal of the C in CSS; without it cascading is impossible (is it good or bad – another big topic for flaming).

List (non-exhaustive) of different methodologies (in no particular order):

- BEM – Block, Element, Modifier

- SMACSS – Scalable and Modular Architecture for CSS

- OOCSS – Object Oriented CSS

- ACSS – Atomic CSS

CSS Modules

We have to step back a little before proceeding to the actual discussion of css-modules, which itself is a specification for loaders.

So, after the success of Gmail and the growing usage of AJAX, applications started to be more frontend-focused, not only by size, but rather by language – javascript. People started to build much more complicated applications, some started to render everything on the client – using templates from javascript, so backend code started to be irrelevant in some cases, so it made sense to decouple them in CVS (like git) as well. It sparked necessity of tools for processing assets, separate from backend frameworks pipelines.

And because node.js was released, people started to build them. Grunt, Gulp, and then, finally Browserify. The last one is especially important, because while Grunt and Gulp perform a set of tasks on files, browserify processes everything based on a set of rules. Essentially, it means that we can process everything, including css, and it means, that we can require css files, and get some output. And it works exactly this way – we require a css file, it is parsed, and we have a normal js object with keys as our classes, but values are different unique strings!

This is an amazing breakthrough, and I would like to stress it once again. We are able to have as many title classes as we want, as long as they reside in different files – which is perfectly fine for us, as we want to keep them nearby to the template/component/UI which actually uses them. CSS modules, in fact, is a concept of having scopes, it is like a block-element system from BEM, where block is unique prefix (and we don’t have to think about it at all), and element is our classes – e.g. title. Because we can modularize as much as we want, and prefix will be unique, we don’t really need to introduce modifiers at all – but we can! We can use the whole BEM naming system again, or use nesting, or absolutely anything, but with being sure that it won’t overlap with something else. This is a very powerful technique!

The biggest downside, which is still unsolved, is sharing code between application and our styles. Using preprocessors, we can define same variables during build step, but if we want to define something during the runtime, we have to fallback to old style attributes, which naturally leads us to the last point – css-in-js.

CSS-in-JS

There was some playing in this field before, but all the buzz started after this talk:

It touched a very dangerous topic about should we move all styles also to javascript, and now there are plenty of libraries to do so, but they all have only 2 different approaches. The first approach is very obvious, they literally use all styles from javascript. There are a couple of problems here:

- there are no classes at all, so you can just tinker around changing styles of all list elements

- looking into the developer console, it is incredibly hard to understand which component is here

- we transfer more bytes – because everything is inlined, we have to repeat ourselves in many places

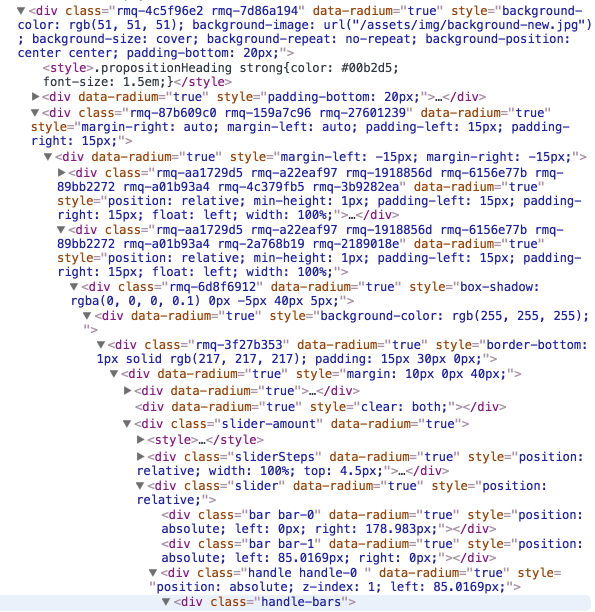

Example of project with inline styles

Example of project with inline styles

The other approach is to use DOM specification about StyleSheets. It works almost the same from the interface part,

Because we literally write normal javascript, it allows us to solve absolutely all the listed problems, and even more – we can transform our styles in runtime, so your application can be styled completely differently based on some parameters, and can even be restyled subtly based on some toggle, which will be a very complicated task in case of using traditional approach, with prebuilt CSS files.

Of course, there are several problems:

- tools are not ready yet. Thanks to the JS ecosystem and community, it is fine for Electron based editors, but more traditionals IDEs will pick it up not that soon (by tools I mean emmet and linting mostly)

- many libraries don’t have any nesting

- it is javascript, so this might complicate development in case less experienced developers are used for HTML & CSS development

- it is a very rapid field (as usual in JS world), so there is a big chance that in couple years your library will be obsolete and abandoned

And list (non-exhaustive) of active projects, in no particular order:

Conclusion

Nowadays, when you start a new web project, you should definitely choose a strategy, based on the size of the application and requirements. If you don’t have to style a lot of stuff dynamically and you know all the variables at the build step, and you don’t want to share some components between different projects with different themes, then you can safely pick a more traditional approach (but I highly recommend to use CSS-modules, to solve all problems with global class names and specificity), using some methodology of your choice, and stick with it. There is a 100% chance, that your choice will still to be sane in the next 5 years, which is a big question in the case of JS choice.

In case you need a big flexibility, heavy theming and maybe some on-the-fly style changings, then go with CSS-in-JS. You will need to evaluate all the existing solutions by yourself, picking which you believe the most, and which suits you the best – it is a risky bet anyway, but it will definitely solve a lot of traditional problems of css, especially with shared components between projects and runtime style changes.